NetNZ meets the needs of today’s learner using the internet as a tool to provide ubiquitous learning which breaks down barriers of time and place. We also have a strong commitment to cultivating innovative approaches to learning for students of our member schools and beyond. In order to do this we have supports in place for teachers to develop their own professional learning as part of a continuous and community focused process. This space is designed to provide support for teachers to direct their own learning.

- Course Design

- Putting it together

- Engaging learners online

- Emergent Design

- Learner-centredness

- Knowledge Building

- Building Community

- Promoting Discussion

- Discussion: Issues and solutions

- Netiquette

- The Video Conference

Putting a course together that is clear, follows a logical structure, promotes student interaction and that develops engaging approaches to learning is no easy feat. The following section is designed to give you some ideas on this.

Planning your online course

Spend some time thinking about how you want your course to work. What sorts of tools do you want to be available for students? For example do you want to be able to gather feedback from students on a regular basis, do you want a place for them to ask questions or discuss ideas, or do you want a glossary of terms? Work out what tools will enable to do this effectively.

The key starting point is to have a centralised online class space and to decide early what you will use for that. Most NetNZ teachers have use google+ communities, but there are alternatives that teachers are free to consider – Google Classroom (Although difficult across schools currently), Edmodo, Schoology are all possible. The key is your approach, rather than what technology you use. NetNZ values the development of community within an online class so the use of google+ communities is a purpose built tool for this sort of approach. Once you have decided what you want on the space start planning it out on paper. Make sure you also spend time reading and watching tutorials to learn more about the tools to use.

Orientation

In a face to face class the usual practice is to launch straight into the content, but we strongly recommend you don’t do this with an online class. Spend two to four weeks on getting students to orientate themselves on the course. This would include:

- Gathering information on the students

- Set them tasks to complete that introduce them to certain tools

- Getting them into google+ and google apps

- Developing community

Gathering information

A good starting point for learning is to first establish the knowledge and skills of your students. As part of this you might like to design a survey or questionnaire that enables you to learn something about your students. Over time I have developed this questionnaire using google forms. All students are required to complete on entry into the course. Feel free to copy and adapt as you see fit. It is an invaluable exercise. You also might design some broad diagnostic testing that establishes students’ prior knowledge and skills. You might get them to do a short essay to examine writing technique or a quiz to determine prior knowledge.

Developing Community

One of the most important aspects of teaching online is developing your students as a learning community. This is a totally new experience for many students who might be quite unused to working with others, but it is an absolute imperative for you. Why? Well…

- You are not there face to face for quick help if they need it. You might not be able to answer a question for a full 24 hours sometimes so it is important they can ask questions of other students.

- Learning by distance can be an isolating experience for students, but it doesn’t have to be. Developing student interaction and collaboration will break down this isolation. You need to develop a sense of being part of a class or group of learners, rather than working entirely independently. The video conference also plays a part in this (see later), but a google+ community can be used to develop ongoing discussion that will ease the stress of learning by distance for many learners.

- Numbers will play a part in this. It will be much more difficult to develop online discussion with a small number of students

We will come back to building an online learning community later.

In order to build a sustainable online community you will need to put in a lot of effort in the early stages of the course. As suggested above, it is worth putting aside the course content for two weeks or so and develop some online discussion using your course forum. Set up some icebreaker activities which require the students to interact. Once all students have spent time on these activities they will feel more comfortable contributing. From here you need to develop opportunities for students to continue discussion based on the work they are doing.

As Palloff and Pratt indicate in Building Online Learning Communities, “…the need for social connection is a goal that almost supersedes the content orientated goals for the course. Students should gather online just as they do on the campus of a university.”

Ice Breaking Activities

Animal Introduction

Create a discussion thread and get everyone (including yourself) to post a reply introducing themselves and some of their interests. In their post each student must attach an image of an animal that represents them and their personality. Students post replies to each other guessing why they chose their animals and what characteristics they might represent. Students could then find another student who has chosen an animal that shares two characteristics they have chosen. Together they could find another animal that shares these two characteristics as well two new ones. They then post this with an accompanying image. Sounds silly, but it works!

Truth or Lies

Each student posts two truthful statements and one falsehood about themselves. Each member of the group then tries to distinguish the truths from the lie. What makes this activity fun is to be as outrageous as possible while sharing a bit of who you really are with your fellow participants. Once all responses have been received students post their truths and explain why they chose to share them.

Snowball

Have one person enter a basic introduction of himself or herself, including his or her interests. A second person must enter an introduction of himself or herself and find one thing in common with the first person. A third person enters his or her intro and finds one things in common with the first and second person. Each of the rest of the class members then enters an introduction and must find something in common with at least three other people. The first person in turn, must respond to at least three people with whom he or she has something in common. The second person must respond to at least two additional people. The third person must respond to at least one additional person.

Overview

It is a good idea to include a few general bits and pieces in the top block of your course as a course overview. Write a general blurb for the course and then place some tools and resources that are relevant. You should include:

- A course outline (as a downloadable resource or as a series of webpages / book)

- A list of course objectives (might be included in the course outline)

- A folder of general resources for the course / NCEA standards, etc. Alternatively you could just add each resource individually. These files could be held on your Moodle course or linked in from a google docs folder

- Useful links

You might like to include:

- A glossary of terms that students develop

- A journal for ongoing student reflection

- A student feedback tool so students can give you ongoing feedback on how things are going

Structuring the learning

There needs to be a clear structure to the learning in an online course. The following outlines a sound, organised and clear approach to structuring the learning. It is not a definitive approach. There is a lot of room to develop your own approach based on ideas you take from here.

In a face to face situation learning is often broken up into discrete lessons in which the teacher introduces the objectives or outcomes for the lesson, sets tasks for the students to complete and perhaps summarises at the end. The approach is different in an online situation, but you have options as the teacher

You could structure the course by:

- Weekly units of work

- Modules which cover one or more weeks

- Topics which may be taught from at different times within the course

Whatever timeline you use for the work each ‘module’ should have a clear structure to follow. The following would be typical of a module of work.

- The objectives (these might be developed with or by the students)

- An overview / explanation of the work

- The tasks to be completed (choices could be available in how or what students do)

- Supporting resources (students could also find and share resources)

- Some assessment of/for learning (this could be informal)

Objectives and Overview

When you add tasks, activities, and resources you can’t expect students to just ‘get it’ without a thorough overview and summary of the work. It is good practice to start the overview with the learning objectives or outcomes for that module or week of work. This establishes what the students will learn by completing the work and provides a clear focus for the learning. Once the objectives are clearly established you can explain the various tasks that are to be completed for that section of work. If there is any sharing or assessment it might be a good idea to explain it here as well. Make the instructions as clear as possible (you don’t want students with too many questions). You might like to think about using a webcam to record yourself explaining the work (as you would with a class). If you are using a google+ community you can do this very easily. This has the advantage of reinforcing written instructions more visually.

Tasks and Activities

You can create and link the accompanying tasks underneath the overview. As with face to face teaching there are many things you could do with your students, but always consider how you develop student interaction and connection. Google docs is a fantastic tool for getting student to work together and can allow the teacher to easily monitor and give feedback if required (this can be done by the students as well)

Add Resources

Now add any accompanying resources. These might take the form of documents you upload to google docs, links to useful websites or embedded videos

Sharing the Learning

Getting students to share their learning is good practice in any context, but it is especially useful in an online course. As mentioned earlier, some students may be a little uncomfortable doing this initially, but if it is a regular activity they will soon get used to it. A google+ community is an excellent place to get students to share and discuss their learning, as is the video conference lesson you have with them each week. Try different things with your students and find what works for you and them.

Assessment

As in a face to face classroom, assessment, and more importantly, formative assessment, plays a key role in student learning. It is good practice to have some form of assessment within a block of work, whether it is at the end or part of the work the students are doing. There are a number of options available to you:

- Any sharing of work is a form of assessment of course and much of what you do might be quite informal. As mentioned previously this could happen in the forum.

- The video conference is a good way to check student learning, especially in the form of student seminars or presentation, but it has limitations in terms of the depth of learning you can judge.

- Google docs allows the teacher to easily assess student learning if give feedback.

More formal assessment should take place as well of course. Regular practice on the NCEA standards (if applicable) is important and again, the assignment tool is an excellent way to this. It also allows you to give feedback to your students as well as indicative grades if you want.

It isn’t necessary to assess everything yourself. A key aspect of developing an online learning community is to get the students sharing and working together. The use of self and peer assessment is especially useful in this environment, where regular checking of work can become quite a burden on the teacher. Why should the teacher be the font of all knowledge? Turn it back on the students. Give them clear marking indicators and get them to assess each other.

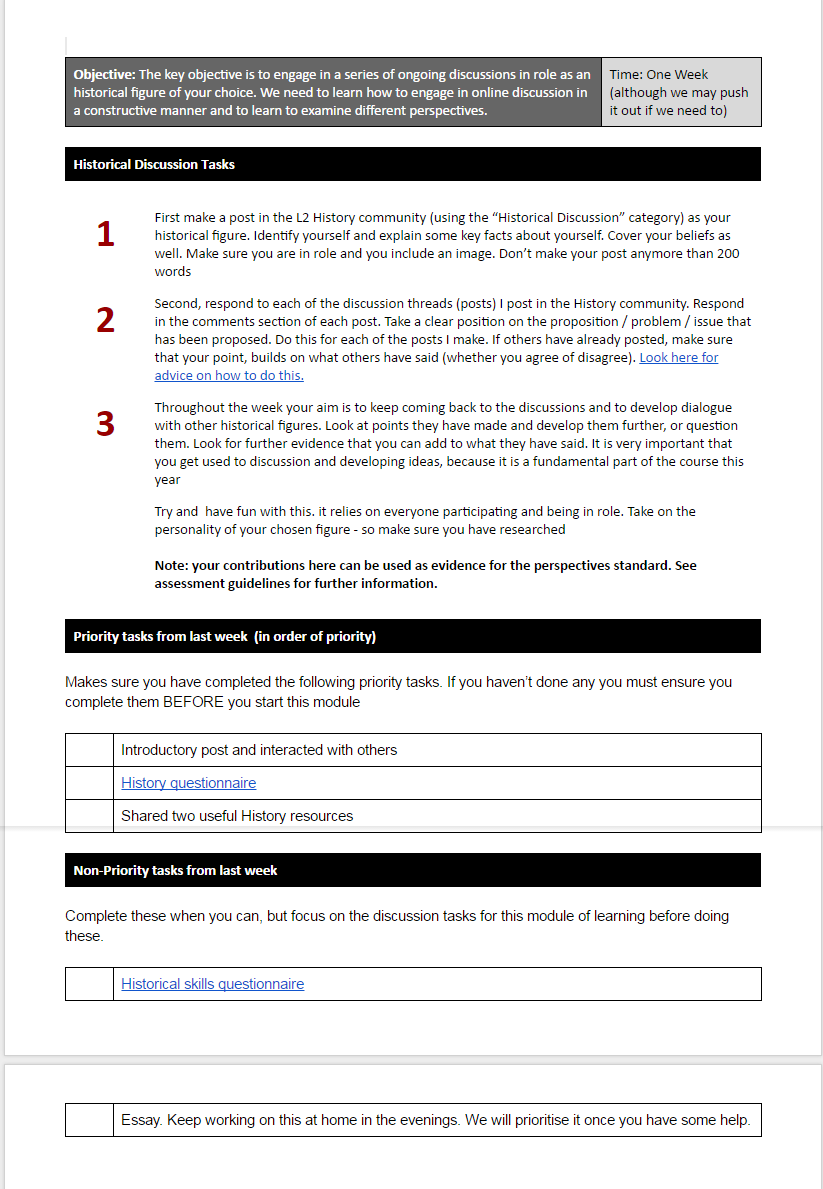

Example Module of Learning

As mentioned in the video below, just putting together a series of resources online that you expect students to work through is not engaging for them. How you design the learning is important when trying to engage learners. Think about the following

- Make it relevant and authentic to the students

- Have a strong social presence online so they know you are there to support them

- Recognise their strengths and interests and construct a course around those.

- Develop student agency. This means that you let them have some control over what, when, and how they do things. Develop a flexible course that allows this to happen. You don’t direct them all the time

- Develop approaches to learning that allow students greater control. Inquiry learning, knowledge building or connected approaches that recognise what students bring to the table. Start pushing the boundaries with your practice.

.

Traditional learning design approaches are very structured, teacher directed and outcome orientated. It is very much about the teacher setting the learning objectives/outcomes, designing tasks for the students to complete and then measuring their learning according to the objectives set. While this has advantages in making the learning very clear for the students there is a significant problem with this approach. An outcomes based approach can be too rigid and flies in the face of the call for more student autonomy in learning. How can it be a truly self-directed learning experience if the outcomes and the paths to these outcomes are pre-selected before the student even signs up for the course?

Emergent design refers to an approach to online learning that is learner centred and directed, flexible, collaborative and based on the use of web 2.0 tools. It has a number of features:

- A flexible approach to course design that allows the teacher to adapt the environment and the tasks based on student need and feedback.

- A collaborative approach to learning where the learners work together to generate content and build knowledge.

- Students have choices on what they will learn and how they will learn it.

- The online environment is co-constructed

- The teacher acts as a facilitator rather than the ‘expert’

In traditional teacher-directed and lecture-based models of learning, the teacher projects information to a group of learners. As you transition to online, you will find that teaching to a group is simply not as effective. You may also find your instruction becoming more personalized according to student needs. Finally, in the full implementation of learner-centeredness, the teacher (now, the facilitator ) provides the structure and guidance that allows learners to create and participate in a network of learning. We can visualize learners making connections, not only with the teacher but with classmates and external sources. We can also see them taking responsibility for their own learning and following individual learning paths that are engaging, motivating, and meaningful to them.

Learner-centredness

Learner-centeredness is about enabling the construction of knowledge based on goals that are important to the learner. It is the recognition of learners as diverse individuals with different interests, needs, and capabilities.

Learner-centered environments inherently provide the capacity to individualize to learners’ specific needs. The structure of online environments can facilitate learner-centered approaches by allowing learners to direct the sequence and focus of inquiry through interfaces that allow flexibility in the completion of tasks. Learner-centeredness is facilitated in online environments with activities that are self-directed, authentic, and incorporate structured decision- making processes.

Learner-centeredness is not a new idea. It has been studied extensively in traditional educational environments. The literature surrounding this ideal of best practice and its application in online environments will be discussed in the following section.

McCombs and Vakili (2005) operationalized the LCPs into a set of practice implications that can be used to guide your teaching practices in online environments:

- Practices should integrate learning and motivational strategies to help students become self-directed learners.

- Practices should include pre-assessments and ongoing assessments of students’ interests, goals, background knowledge, and needs to better tailor practices to each individual.

- Mechanisms should be in place to better connect other learners in learning communities and/or communities of practice.

- Students should be involved in co-creating instruction and all instructional experiences with their “teachers” and others in their learning communities.

- Practices should address both community and individual personal needs; community is not defined geographically, but by shared interest in the subject matter and adaptability.

- Concepts of “emergent” curricula are at the heart of the system; each learner or community of learners can, at any period of time and based on their needs/purposes, create curricula that include dynamic and up-to-date information.

- Curriculum should be customized based on pre-assessment and ongoing assessment data to allow learners the opportunity to see the progress they are making.

- Curriculum should be flexible and dynamic, with a minimum of structure based on student needs and/or developmental considerations.

- Feedback should be available for student review “on call,” so that it can be used for self-evaluation of progress; it is available for others to see when students are “ready” to submit work; feedback provides ways for students to remediate and enrich their knowledge and skills in areas of choice as

appropriate. (p. 1587)

Learner autonomy, or the ability to take responsibility for one’s own learning, is a desirable characteristic for all learners. Self-regulating learning strategies have been found to have a positive relationship with the ability to think critically and use metacognitive strategies in online learning environments, which in turn

may lead to higher gains in achievement (Artino & Stephens, 2006; Kawachi, 2003; Meyer, 2003).

Traditional learning aids—such as the use of modeling, prompting, and coaching—are tools often used to teach strategies for reflective thinking and problem solving, with the ultimate goal being a gradual release of responsibility to the learner. Online environments can encourage learners to take initiative in their own learning by seeking out information and building connections. Lee and Gibson (2003) suggest that independent learning “can be developed in an online environment if that environment is designed and facilitated in ways to encourage dialogue, provide flexibility in structure, and allow students to take some responsibility, assuming some control in a critically reflective way” (p. 186 ). Providing additional resources, allowing choices in completion of tasks, and establishing private and collaborative spaces for dialogue allows learners flexibility for explorations in line with their personal interests, either on their own or in conjunction with others.

In the 21st century we are facing numerous unprecedented social, political, economic, health and environmental challenges. To produce innovative and creative solutions to these so called “wicked problems” we need to increase and democratise the knowledge creating capacity of our society (Rieckmann, 2012). In Education, there is an urgent need to design pedagogical practices, and create new learning opportunities to develop young people’s innovative capacity (Lai, 2014a). Instead of focusing on reproducing knowledge, students must be able to “actively interact with [knowledge]: to understand, critique, manipulate, create, and transform it” (Bolstad & Gilbert, 2008, p.39).

Knowledge Building promotes key principles which are designed to meet the growing need to re-imagine how schools meet emerging challenges. Scardamalia (2002) describes twelve key principles which together promote learning as a process based on curiosity, exploration and questioning, of improving ideas as a community of learners, and encouraging student ownership of the learning process and real world problem solving. It is a process that should be an integral part of the paradigm shift that needs to occur in education. It also places values such as “innovation, inquiry, and curiosity”, identified as integral to the New Zealand Curriculum, at its very centre.

NetNZ has a strong commitment to developing knowledge building approaches to learning. Every year we run at least one project designed to develop and support a knowledge building community of practice. See some examples from teachers in 2016. If you would like to know more about knowledge building go to the Knowledge Building NZ website.

Social presence, in simple terms, is how much learners feel they are part of or belong to a community (Picciano, 2002). Using this concept allows us to extend the conversation of transactional distance and apply it in a social context. Social presence is a concept that researchers and theorists have used to explain the feeling of connectedness learners have with their peers and teachers in online courses—in other words, their sense of community. The idea of social presence is important because it has been found to influence learner satisfaction, retention, and learning (Rice, 2006).

When thinking about this concept, imagine yourself teaching in a traditional classroom. You would not expect learners to navigate the course content on their own. You would perhaps begin a lesson by presenting core knowledge using direct instruction, move to guided practice, and finish with a project or assignment, providing assistance and guidance through to completion. If the lesson were more constructivist in nature, you might begin with an exploratory activity, allowing learners to investigate the topic through a Web-based research project (e.g., scavenger hunt, WebQuest), gather information, and present their findings to the class while you provided guidance and corrected misconceptions. During either of these activities, students would have opportunities for interaction in the forms of discussions, questions and answers, and/or group work.

The essential element in both of these lesson examples is the influence of social presence on learners’ sense of belonging, formation of community, and opportunities for enhanced learning, which, in turn, fuel learners’ engagement with the content and with each other. Even though community formation is somewhat intuitive in face-to-face classrooms, in online settings, it takes a concerted and consistent effort to provide the same opportunities.

When we talk about community, then, we are talking about the feeling of belonging. This concept applies within the walls of the classroom (virtual, though they may be), as well as outside those walls. A major benefit that online environments have over traditional brick-and-mortar environments is that they allow us to easily negotiate connections within local, national, and global networks,

Strategies for Building Community

Traditionally, education has been viewed as a social process. Interaction and discourse have typically been seen as critical to learning, to the development of higher-level thinking skills, and to the acquisition of knowledge. Yet the importance of the social aspects of education has probably never been debated more vigorously than since the Internet began to be used for teaching.

The primary reason for the debate is the perception that student isolation is a drawback of online environments. With the improvements in social and networking technologies, incorporating opportunities for learners to make connections has become less of an issue. The challenge is more often in our willingness to provide opportunities for learners to do so.

Establishing community within your classroom can be as simple as being aware of how often you communicate with students and what tone that communication takes. Not surprisingly, the quicker your response time and the more often you communicate, the greater your sense of community will be. Using humor, expressing emotions, communicating informally, asking questions, complimenting, and expressing appreciation are all strategies that can help you increase the sense of community in your classroom (Lowenthal, 2009).

It may seem obvious, but community does not happen on its own. You will need to work consciously and consistently to develop and maintain it throughout your course. Doing so involves demonstrating a strong presence in the course, including activities for building social presence early on, providing support for learners new to online environments, and designing interpersonal interactions into the course (Kehrwald, 2007).

These simple strategies can be implemented immediately:

- Get acquainted with learners by asking them to share photos, biographies, and interests. Before asking students to introduce themselves, introduce yourself.

- Use icebreaker activities to facilitate the identification of common interests among students.

- Make student profiles visible and ensure students have an image of themselves or representing themselves in their profile. This is far better than a faceless silhouette that is the default.

- Incorporate audio or video messages using slideshow-sharing tools, such as Screencast, and animated avatar tools, such as Voki. Also use free audio tools, such as Audacity, to create podcasts.

- Ensure students use the google+ community or discussion board to ask questions. Do not reply to emails unless they are of a private nature. Make it a rule that this is where students are to no post and resist replying to emails.

- Contribute to discussions judiciously to allow students’ voices to dominate.

- Contribute to the social discussion by starting a conversation and be open to sharing personal stories and experiences.

- Let your personality shine through and encourage students to do the same by using humor and emoticons in your communications. Always remember to address students by name and consider allowing students options for addressing you.

| Ice Breaking Activities

Animal Introduction Create a discussion thread and get everyone (including yourself) to post a reply introducing themselves and some of their interests. In their post each student must attach an image of an animal that represents them and their personality. Students post replies to each other guessing why they chose their animals and what characteristics they might represent. Students could then find another student who has chosen an animal that shares two characteristics they have chosen. Together they could find another animal that shares these two characteristics as well two new ones. They then post this with an accompanying image. Sounds silly, but it works! Truth or Lies Each student posts two truthful statements and one falsehood about themselves. Each member of the group then tries to distinguish the truths from the lie. What makes this activity fun is to be as outrageous as possible while sharing a bit of who you really are with your fellow participants. Once all responses have been received students post their truths and explain why they chose to share them. Snowball Have one person enter a basic introduction of himself or herself, including his or her interests. A second person must enter an introduction of himself or herself and find one thing in common with the first person. A third person enters his or her intro and finds one things in common with the first and second person. Each of the rest of the class members then enters an introduction and must find something in common with at least three other people. The first person in turn, must respond to at least three people with whom he or she has something in common. The second person must respond to at least two additional people. The third person must respond to at least one additional person. |

Promoting Student Interaction: Co-Construction

Co-construction of learning is an integral aspect of an effective online course and is the key element that distinguishes online learning from traditional face to face. Getting students to interact at a distance is a challenge, but an important one to tackle in order to reduce the sense of isolation for most students. It will also provide a better learning experience for the students themselves.

There are several ways you can promote student interaction:

- As mentioned earlier – in the forums

- Getting students to build a glossary of key terms using the glossary tool

- Use Google Docs to get students creating presentations or documents together. These can then be posted in the community

- Use padlet for student brainstorming or visual/text presentations

- Use Voicethread for sharing of knowledge, presentations, resource interpretation (all sorts in fact)

- Use mindmapping sites like mindmeister or bubbl.us to get students working together to process information visually

- There are many more web 2.0 tools out there you could use and many of the can be embedded into your Moodle course. Like any web 2.0 application they are designed to be used collaboratively so why not get your students to use them?

Rationale for Using Discussion Forums (or google+ communities)

There are a host of benefits to online discussions, beyond the obvious community-building benefits already discussed. Quiet students who find it easy to avoid detection in a face-to-face classroom often enjoy participating in online discussions, because they can contribute at their own pace and have time to reflect on their contributions. Some of the more typical social and status constraints that influence face-to-face discussions are absent from asynchronous discussions. For example, issues of race, gender, accent, and status often do not come into play. Other more instructional benefits that have been identified by researchers include opportunities for constructing and negotiating meaning, promoting critical thinking, achieving higher levels of abstract cognitive processes, providing careful formal and reflective responses, and being motivated to write well due to the presence of a real audience and purpose for communicating.

The archival quality of text-based discussions also makes them attractive for accountability purposes, given that everything is documented in writing. Whether your discussions are a success will depend greatly on thoughtful consideration of a clearly defined use. In a broad sense, online discussions can be divided into three primary types according to use:

- Social forums can be used to promote social interaction and facilitate community building. These types of forums provide opportunities for learners to share personal experiences and to find common interests.

- Instructional forums centre on the subject matter goals and objectives of the course. They are used to support learning through various methods, such as collaboration, problem solving, and critical thinking.

- Collective knowledge forums provide opportunities to tap the expertise of class members. Examples might include “Tech-Help” forums and “Think Tanks,” in which classmates ask questions and receive assistance from their peers. This type of forum can be a valuable resource for the class and encourage a participatory culture, in which all members of the community are valued for their varied areas of expertise.

Of course, there are no hard-and-fast rules here. There can be some crossover among all three types of discussion forums. For example, discussions that employ the group’s collective knowledge for peer-assisted troubleshooting and other forms of technology assistance may fall into one of the other categories, depending on the instructional objectives of the class.

Preparing for Online Discussions

As with any online activity, it is important to spend some time thinking about where a discussion will be conducted and why a discussion is chosen as the instructional strategy versus another strategy.

Physical Structure of Discussion Forums

In the book Essential Elements: Prepare, Design, and Teach Your Online Course , Elbaum, McIntrye, and Smith (2002) suggest that structuring your communications within the course site is a key element for success. Doing so will allow you to clearly delineate specific uses, provide for documentation, and facilitate easy retrieval of student questions and responses.

Often, the issue is not how discussions are facilitated but a lack of understanding about the purpose of discussion forums. Just because online discussions are text based does not mean they should be essay oriented. If we expect learners to engage with each other, with us, and with the content, we must provide them with something worth engaging about. This begins with the discussion prompt.

The topics addressed in instructional discussion forums should have instructional relevance. They should relate to, expand on, or otherwise support the content and objectives of the unit being studied. However, the question being posed should be one that can be discussed easily and that promotes interaction, interest, and curiosity from learners. In other words, discussion should be an integral part of course goals, not an add-on assignment (Fischer, Reiss, & Young, 2005).

Critical thinking is at the core of instruction and learning in any environment. Specific strategies can be employed in online discussions to sharpen the focus and dig deeper into learning. Again, the discussion prompts are critical:

Good questions are the key to productive discussions. These include not only the questions you use to jump-start discussions but also the questions you use to probe for deeper analysis, ask for clarification or examples, explore implications, etc. It is helpful to think about the various kinds of questions you might ask and the cognitive skills they require to answer.

When creating discussion prompts, consider including learners in the process by providing opportunities for them to take the lead in discussions, to suggest possible questions they would like to discuss on a topic, and to choose questions or prompts from a bank of questions you provide. If your curriculum provider gives prompts for you, take advantage of opportunities to extend thinking through your follow-up questioning strategies.

Strategies for Effective Discussion Board Facilitation

Effective facilitation involves a host of activities. The strategies discussed in the following list draw from an extensive knowledge base of what we know about effective discussion facilitation in face-to-face environments, the literature on discussion board facilitation for adult learners, and emerging literature on discussion board facilitation for K–12 learners (Collison et al., 2000; Elbaum et al., 2002; Rose & Smith, 2007):

- Identify the purpose of your discussion forum, and make students aware of it.

- Provide appropriate scaffolding, guidance, and resources for learners who are unfamiliar with text-based communications. Do not assume that learners come to your class knowing how to communicate effectively in instructional discussion forums. Model appropriate responses using questions to probe for deeper learning, offering descriptive comments, providing constructive

criticism, posting early, checking in, asking thoughtful questions, responding respectfully, using personal experiences, and verifying appropriate grammar and spelling. - Encourage peer participation, review, and feedback by establishing the expectation that learners are the central focus of the discussion. Instead of trying to respond to each student, post occasionally and thoughtfully.

- Establish this pattern early on, so that learners understand your intentions. (This applies to almost all cases except in the case of introductory activities where you should make a concerted effort to respond to each and every student.)

- Establish protocols that assure learners you are reading every post, even if you do not respond to every one. Do not just tell learners this. Show them through summarizing, highlighting selected posts, and providing frequent encouragement (not praise).

- Differentiate your role within discussions. Some will require extensive involvement, whereas others will require very little. Similarly, differentiate your voice and tone, depending on the purpose of the discussion.

- Avoid public praise of contributions. Instead, reflect student ideas and foster deep exploration of content by highlighting posts that are on the right track. Summarize two or three posts, and pose an additional question that challenges the learner to dig deeper.

- Improve the quality of the discussion by making available preparatory reading materials and preassignments, or ask learners to provide resources to support their points of view.

- Refrain from using discussion forums for self-reflection, questions that require right or wrong answers, essay or short-answer responses, and yes/no responses.

- Use discussion posts as a resource. Consider how you might use the extensive content created in discussion forums to provide further learning opportunities for students.

Managing Online Discussions

You have established a clear purpose for your discussion, created a thoughtful and engaging prompt, and employed effective strategies for facilitation. But what if you are still experiencing less than satisfactory results? No matter how well you prepare for online discussions, you will always face the possibility that you will not get the results you expected. Discussion forum management issues come in a variety of forms—from simple organizational concerns, such as time management, to more complex concerns that

surround student behavior.

Time Management Issues

One management issue that affects all of us is time. Every teacher feels the time crunch. Sometimes, it seems there are not enough hours in the day to get everything done. With careful planning, you may not be able to make more time, but you can make better use of the time that you do have:

- Set aside time for each communication activity each day. Create a schedule

with blocks of time specifically set aside for responding to student discussions. - Prepare posts in advance. Introductory posts and responses to icebreaker activities can usually be prepared well in advance and used over and over with small revisions.

- Save your past posts. Often, the same questions, issues, and conclusions occur repeatedly from term to term and class to class. Create a master course discussion document with your most frequent posts. They usually require only quick updates to make them current.

- Use students, parents, and other support mechanisms. Fear of inappropriate, dangerous, or life-threatening communications can hamper efforts to incorporate discussions into online classes. If you experience anxiety about your inability to monitor a large number of posts effectively, use other responsible individuals as moderators to alleviate your concerns

Common Discussion Forum Management Issues and Solutions

All teachers fear the out-of-control classroom. In fact, it is a common belief that teaching online allows avoiding all of the discipline and classroom management issues found in face-to-face classrooms. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Of course, the most effective preventive step for many management issues is preparation. For online classes, that includes the creation of purposeful and meaningful discussion board activities. A second defense is being prepared for the issues you may encounter. Solutions to some of the most common issues are provided in the following list:

Problem: Nonparticipation

Online courses are notorious for high levels of non participation and attrition. Monitoring participation in online discussions is critical, especially with middle and high school students, who may not be closely monitored by an adult at home. Independence, autonomy, and self- regulation are not universal skills. Even students who are otherwise engaged may exhibit non participatory behaviors in online discussions.

Solution: First, try to determine if there is a cause unrelated to engagement with the course. Lack of Internet access, technical issues, and life issues may prevent students from participating in ways they would like. Recommend an alternative location, such as an after-hours school computer lab or a library where students may find access. Second, ensure that learners understand what is expected of them (Wu & Hiltz, 2004). Walk them through the process, step by step. Third, review your course design and add additional guidance and resources in course activities. Make sure learners are aware that lack of participation does not excuse them from completing an assignment. Create alternative assignments for learners who are unable to make up discussion activities, due to lack of participation.

Problem: Writing too little

This can be an issue at any age—from very young learners to adults. Learners have a natural tendency to meet only the minimum expectations requirements for an activity or assignment.

Solution: Clearly articulating the purpose and relevance of an assignment to learners’ lives outside school can increase their engagement with the content. Provide examples of acceptable responses. Also consider providing examples of what not to do to highlight the differences. Negotiated outcomes can provide added incentive and motivation for learners.

Problem:Visiting a forum only once

Some learners will participate but do so in a single visit and never come back. This defeats the purpose of ongoing discussions, interactions, and engagement that you are trying to create.

Solution: Setting clear expectations for participation is critical. Make learners aware that regular, consistent interaction is required for meaningful discussions to occur. Require them to post a minimum number of times per week, or request that they respond a minimum number of times to classmates. Set up variable due dates over the course of the week. For example, require an initial post on Tuesday and a response to a classmate’s post on Friday. Try to refrain from closing discussion forums on the due date. Rather, expect that discussion forums will extend past their due dates to allow for last-minute posts. Adjust your due dates to allow for this inevitability.

Problem: Generic replies

Learners may post only generic replies, such as “Hey, great post” and “Wow, you’re awesome.”

Solution: Even when given clear expectations about the content of posts, learners may not be comfortable critiquing, providing opinions, or reflecting deeply on content. These behaviors must be learned and practiced. Provide opportunities for learners to practice their skills and assess them on it. For example, create a sample discussion in which students work together to create appropriate, high-quality responses at the start of class. Provide models of exemplary posts, and use questioning strategies to

prompt deeper learning.

Problem: Small number of participants

Having a small class can limit the quality of discussions simply because there are fewer participants (Vrasidas & McIsaac, 1999). If discussions are spread over a week, there will not be enough activity to keep the discussion going.

Solution: As a general rule, there should be at least 10 to 12 learners in a class to have an optimum level of input. If you have such a small class, be thankful. Clearly, it is much easier to provide personal attention to a small number of learners than to a large number. Increase the activity in a small class by incorporating discussions into collaborative activities.Also allow learners to meet with partners or small groups, rather than participate in whole-class discussions. Their work will be more focused and individualized.

Problem: Writing/reading skill or quality is poor

Learners with poor writing skills are at a disadvantage in textbased communications, and they may be afraid of opening themselves up to ridicule and judgment by classmates. Try to prevent problems from occurring, and prepare alternative strategies for these learners. Very young students also fit in this category.

Solution: The use of speech-to-text and text-to-speech software can provide an effective solution to this problem. If resources do not allow the purchase of a proprietary application, this capability is built into both PC- and Mac-compatible operating systems. Allow learners to use audio recording software to create an audio file such as a podcast. What is important is the content of the discussion, not the media used to share the message. Consider enlisting the help of an adult or tutor to act as proxy or to assist in proofreading and editing. For very young learners, be prepared to instruct parents on appropriate ways to record their child’s responses. It can be hard for parents to refrain from including what they know or prompting the child in some way.

Problem: Inappropriate comments and/or language

You should not immediately assume that what is perceived as an inappropriate comment was intentional. It takes time and practice to become skilled in online discussions, and learners do not always think about what they are actually saying before posting. Learners may not understand how their comments could be taken in a negative way.

Solution: It is critical that you diligently moderate student discussions, so you can identify and remove offensive content. (Always maintain the right to remove any comments you consider offensive.) Provide students with ample opportunity to practice writing and reflecting on their posts. Have them practice reading aloud, since hearing words spoken aloud can sometimes produce better understanding. Provide opportunities for peers to proofread or review responses before they are posted. From the start, be direct and honest with students about what is and is not acceptable. With older students, assign discussion leaders who are responsible for monitoring, or incorporate self-monitoring strategies.

Problem: Inclusive, exclusive, and bullying behaviors

Cliques and behaviors that exclude individuals from a group are fairly typical in the upper grades. Youths love to partner with their friends, and in most cases, doing so is not harmful. In fact, exclusion tends to be less of an issue in online courses, because learners usually live in a wide variety of geographic locations. In addition, the lack of visual cues puts everybody on equal footing. Even so, you must be aware of the potential for disruptive and damaging behaviors, for both ethical and legal reasons.

Solution: If you notice learners intentionally excluding certain individuals, bullying them, or engaging in other harmful behaviors, respond in accordance with your school’s or organization’s reporting protocol. Save all documented evidence of the behavior, and report the incident if necessary. If the problem does not require disciplinary action, try to structure your activities in a way that restricts favoritism and promotes heterogeneous, small-group collaboration. Practicing random group selection is one example. You can allow learners flexibility in forming groups but not make group members known until selections have been made. You can also designate discussion partners and small groups. Require learners to respond to one set of classmates in one post and a different set of classmates in the next. Finally, try to have learners subscribe to the discussion via email, so that their posts will automatically go to the whole class. This can be overwhelming with large numbers of students, but it is manageable with a small class.

Problem: Continuous enrolment

Some programs have continuous or rolling enrollment, allowing learners to enter a course at any time. Although this provides learners with the ultimate flexibility, it can hamper instructors’ attempts to engage learners in meaningful discussions with classmates.

Solution: This type of enrollment obviously creates a difficult situation and often results in weak discussions. Try arranging small-group discussions with learners who are on the same track. Also create a so-called running discussion, which is ongoing and requires learners to build on what has occurred before. Writing Roulette is another strategy that allows for continuously adding to a long-running storyline.

Common Errors When Conducting Discussions

Remember that online discussions are intended to facilitate interactions between students, rather than single responses from the teacher. Online discussions should produce the same outcomes you would expect from face-to-face discussions: deeper learning, higher levels of thinking, and group interaction. Plan your lessons to facilitate this type of purposeful engagement. It is also important to understand that some of the most common errors facilitators make when conducting online discussions are the same types of errors made in facilitating face-to-face discussions

- Asking too many questions at once . Although this is less of an issue in online discussions, it is possible to post a response to a learner that asks more questions than he or she can possibly answer in a reasonable response.

- Asking a question and answering it yourself . Even online, teachers tend to provide the correct answer when they see learners failing to discover it on their own.

- Failing to probe or explore the implications of responses . This is probably teachers’ most common mistake of all. Sometimes, it is just easier to take students’ responses at face value, rather than ask students to explore the implications of what they say.

- Asking unconnected questions . All teachers have likely been guilty of this at one time or another. Asking unrelated questions distracts learners and leads them away from the core objectives and goals.

- Asking yes/no or leading questions . Asking these types of questions ultimately leads to having flat and uninspired discussions. Use other forums or surveys for these types of questions.

- Ignoring or failing to build on answers . Be sure to acknowledge the value of learners’ contributions. This does not necessarily mean responding to every student. Rather, highlighting and summarizing learner contributions can be effective.

When preparing students to learn, teachers in regular classrooms frequently communicate expectations such as rules for the classroom, how and when assignments are to be completed and turned in, and appropriate ways of interacting, such as raising your hand to talk. Online teachers also have to

establish the cultures of their online classrooms. One of the keys to creating the desired learning environment is to use online tools in ways that foster your unique classroom culture and climate.

Netiquette is the term used to refer to etiquette, or rules of acceptable behavior, on the Internet. The practice of netiquette should extend to email, chat, and discussion boards and even into the synchronous environment. As an online teacher, you should educate yourself and your students about using good manners on the Internet.

One of benefits of using the Internet for learning is being able to use social and peer-based interactions to promote powerful and deep learning. Teens, especially, can crave interaction with their peers. Online teachers can draw on this natural desire and tendency by providing a classroom climate, expectations,

and norms that allow learners to interact and collaborate in positive ways while simultaneously supporting their learning (Dawley, 2007).

The key elements of netiquette are similar to the behaviors you would expect in any well-managed classroom. Virginia Shea (1994), author of the classic book Netiquette, outlined 10 easy-to-remember rules for online communications that are still applicable today (pp. 32–45 ):

- Remember the human. Never forget that your email, discussion post, or feedback is being read by someone who has feelings and that those feelings can get hurt. Never post anything online that you would not say to someone’s face.

- Follow the same standards of behavior online that you follow in real life . Put simply, be ethical and do not break the law. Two examples for consideration are laws about privacy and copyright.

- Know where you are in cyberspace. Netiquette varies from domain to domain. For example, the use of Internet lingo or acronyms in an online game may be unacceptable in an instructional discussion forum. If you are unsure, spend some time “lurking” in a particular domain to get a better understanding of acceptable behaviors.

- Respect other people’s time and bandwidth. The Internet does not revolve around you. You may be operating in emergency mode, but do not expect others to feel the same way or to respond immediately to your requests. The same general guideline also applies to discussion forums and other activities in online classrooms. There is life outside the classroom, and you should

respect the boundaries of participants. Be reasonable in your expectations of timeliness, in your approach to copying others on communications, and in how you provide attachments. - Make yourself look good online. You will be judged by your writing, so make sure you write well. Know what you are talking about and make sense when doing so. Also, be pleasant and polite, and do not use offensive language.

- Share expert knowledge. The participatory Web is an amazing place, because everyone gets to have a say in something. Share what you know with others.

- Help diffuse highly charged emotional situations that may include derogatory comments ( flaming ). Netiquette forbids the perpetuation of flame wars. Remember that capitalizing every letter in a word constitutes shouting and so should be avoided.

- Respect other people’s privacy. Private communications should remain private. Today, this applies to texts on mobile devices, as well as email communications and private chat discussions.

- Do not abuse your power. Some people are experts at using various technologies or hold positions of power (e.g., technical support personnel, IT administrators). Do not take advantage of others who are not as well versed in these areas.

- Be forgiving of other people’s mistakes. Be kind when you see spelling errors, absurd questions, and unnecessarily long answers. Give everyone the benefit of the doubt, and think twice before calling out errors or responding negatively with feedback. If you do inform someone of a mistake, do it privately.

There is no definitive approach to a video conference/hangout lesson. Some teachers treat it like a tutorial, while for others it looks much more like a structured traditional lesson. You will need to decide on the approach that fits your needs and you are comfortable with, but there are some things to keep in mind. It is important to keep in to use the session to do the things you can’t do outside of it. It is an extremely good opportunity to develop conversations and that point of connection which face to face learning offers. We now have two main ways of holding synchronous sessions – through a google hangout, or if accessing a course from a north island VLN cluster then a polycom video conference unit.

There is no definitive approach to a video conference/hangout lesson. Some teachers treat it like a tutorial, while for others it looks much more like a structured traditional lesson. You will need to decide on the approach that fits your needs and you are comfortable with, but there are some things to keep in mind. It is important to keep in to use the session to do the things you can’t do outside of it. It is an extremely good opportunity to develop conversations and that point of connection which face to face learning offers. We now have two main ways of holding synchronous sessions – through a google hangout, or if accessing a course from a north island VLN cluster then a polycom video conference unit.

Some tips

- Be very organised. You cannot ‘wing it’ in a video conference/hangout session. Students should receive a plan of the lesson well in advance so they know what to bring, what their role will be and what will be covered. You need your students prepared and if a plan of the lesson is sent out there are no excuses. You will find your students will come to appreciate this.

- Don’t be a talking head. Every now and then it might be necessary (prep for assessments and exams perhaps), but the VC/Hangout is an important opportunity to connect your students. Students new to VC/Hangout will often be unwilling to get involved in discussion, but they will soon get used to it. Make sure almost every lesson has time set aside for the students to interact.

- Do the things in the VC that you can’t do with the students online. Don’t try and go over all the work covered in the week, it just won’t be possible. Pick the key aspects based on the learning of the students. What difficulties have they been having? Is there a key part of the work that requires some reinforcement? Is there a chance for some practical work? Think very carefully about how you will use your lesson, because that time is valuable.

- Don’t let the students sit there passively, because many of them will if you let them. Learning is best in when it is active so use names to call on specific students to answer a question or to give their thoughts. Don’t just wait for anyone to answer or a few will dominate discussion. It’s a good idea to let students know what their specific role will be before the lesson.

- Ask students to keep the mute button off (unless it is an especially large class). Though you might get some annoying noise in the first few lessons, students will soon learn how to reduce this. Having the mute button on allows students to disconnect from the lesson far too easily.

- Make the lesson varied. Don’t spend all your time on one task or activity. Change it up.

- Use the lesson as a way for students to demonstrate their learning/knowledge. Get them to do short presentation or seminars. I have found this works extremely well.

Asking and Answering Questions

- Asking and answering questions is at the heart of much of the interaction that takes place in an educational context. When taking place via video conferencing it can be a little harder to get discussion going.

- Ask various types of questions – planned and spontaneous, high and low-level.

- Remember to pause long enough to give them a chance to consider their answer AND reply.

- Answer the person who has asked the question directly (and by name).

- Remember that you need to direct your answer to the camera – in view.

- Answer concisely using spontaneous writing or other visuals if they help.

- When asked a question, instead of answering immediately you could ask questions to see if they can answer it themselves.

- Try and get a discussion going between sites to obtain an answer.

- Turn to another site and ask a student there to help.

- It is important to find something positive in every answer so the experience of communicating via the link may be encouraging rather than off-putting.

- You may find that you cannot tell who asked a question if it came from the remote site. Don’t be afraid to ask!

You are an important visual image!

A number of rules apply:

- Try not to think of yourself as being on camera, just behave and talk naturally.

- There is a tendency to make sessions very formal but they will be enjoyed more if you smile and crack the occasional joke.

- There is no need to shout or even raise your voice.

- Your normal appearance is fine for video conferencing but small patterns, checks or fine stripes and so on will make your image appear blurred..

- Show you are listening when the remote students talk. Some useful techniques include leaning forward, nodding your head, looking at them by looking at the camera. Facial expression is an invaluable tool!

Effective Strategies in the Video Conference Lesson

Effective Strategies in the Video Conference Lesson

(Collaborative document developed by eTeachers)

- Get students to demonstrate learning by getting them to do a seminar on a topic of their choice. Could be supported by a slideshow. Encourage other students to ask questions. Advantage is that students are prepped beforehand and know what is coming. No hiding.

- When checking “homework” activities, select a student to answer the first question and have that student select a student from another site to answer the next question (this strategy is very good for engaging students and students get to know names and where students are from very quickly) – builds good working relationships in the class

- Encourage students to discuss the topic in line or in context with their ‘local environment’ (this strategy encourages them to view the world around them and link their knowledge)

- Similar to above but also send them a list of questions on something and then throw the questions into the group randomly choosing, so they don’t know which question you are going to ask.

- Pre-quiz on points from the last session at the start of the lesson. General or randomly targeted.

- Post-quiz on the end of a lesson on what’s been covered. Especially on what is required for the next lesson or what and when for next deadline.

- Question basic concepts. e.g. What causes a shift along a demand/supply curve? Define Market Demand. What is Ceteris Paribus? etc. (L1 Economics)

- Quick quiz on topic terminology/features. Backed up by viewing a video clip and writing down where the terminology/features appear (sometimes watching clip through twice). Discuss what students saw, where and how it was used. (L2 Media Studies)

- Send out vocab game cards by email and play games like “I’ve got ….whose got ….. to start the VC lesson – but remember to bring a master sheet along to cover any absences

- Students can build models in their class time but bring them to demo in VC class

- Get students to show what they are interested in: play music, show art works, etc. This enables other students to see and share interests.

- Direct questions … so all students have to provide an answer …

- Ask students to communicate non verbally occasionally, e.g. Place yourself in relation to your seat to indicate how comfortable you are with this topic/skill/concept (might sit on it or move to edge of camera view); if more than one student in a location may use a similar activity for pairs.

- Share an image of the above in the review of the topic to show progress with humor, or repeat the activity.

- Point to specific parts of a model as part of a demo (see 11) or feedback test (e.g. parts of the student’s own body in anatomy, or model)

- Choose 1-2 students per session for teacher to bring in something that is personalised to each one from other parts of the course, web presence etc. Over time cover whole class systematically without making it too obvious or taking up too much time.

- I try to use the VC sessions as a university style tutorial – so students are expected to have completed the work prior to VC sessions. To cope with this my VC week runs from Wednesday to Tuesday.

- Role playing – for example in languages choose one person to be the waiter and ask the other students what they would like to eat or drink, and then repeat their order back to them.

- Hot Seat – like role play, one of the students is assigned a role for example a famous person in history, the students have to ask him/her questions to find out their identity. Alternatively the student in the hot seat doesn’t know their identity and has to guess who he/she is by asking questions of their classmates

It is important to remember to ask yourself some important questions when determining whether a lesson should be delivered live:

- Is the lesson uniquely suited to synchronous learning? Or can it be effectively delivered via dissemination of a document, a post or even a recorded lecture?

- Is there agreement among the participants that every effort will be made to contribute meaningfully to the experience? This includes awareness by all parties that everyone’s time is valuable and that their time together should take advantage of that fact.

- Does the lesson replicate traditional, instructor-led activities, or does it take advantage of new avenues of exploration in teaching and learning? An uninspired slide show lecture delivered face to face will be similarly unappealing (if not more so) in the online environment, where the opportunity for distraction is greater (Finkelstein, 2006).